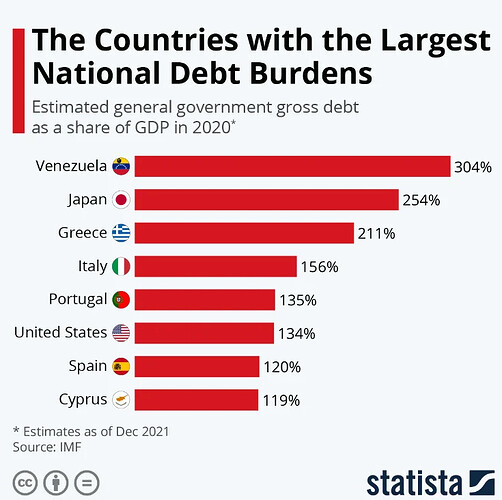

I studied economics and work in the markets. In 2020, these countries had the highest debt-to-GDP ratios. I’m using this chart because (a) I don’t feel like pulling data from the World Bank right now, and (b) four years have passed, yet nothing has changed for these countries.

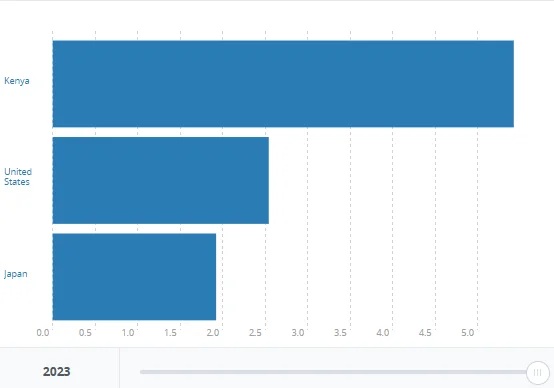

The US, the world’s largest economy, ranks sixth in global debt levels, while Japan, a G7 nation, holds the second spot. Several European countries, including Portugal, Greece, Cyprus, Italy, and Spain, also have high debt. Venezuela experienced hyperinflation due to excessive money printing. My point is that both strong and weak economies can exceed the recommended 55% debt-to-GDP ratio. Below is a chart showing Kenya and USD GDP growth rates since 1961.

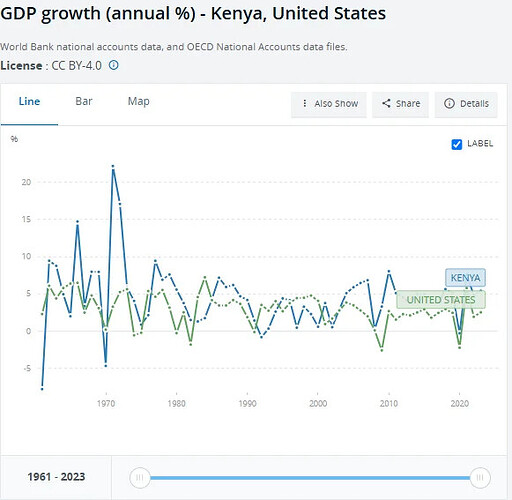

Kenya’s economy has been growing faster than the US, where the debt-to-GDP ratio is over 100%. However, our reliance on the World Bank and IMF means we face more scrutiny before receiving funding. Despite this, Kenya’s GDP is strong, and I recently spoke with a US investor who mentioned that frontier markets like Kenya are attracting interest. In the coming years, we could see significant foreign investment as institutional investors seek high-return opportunities beyond the US and EU.

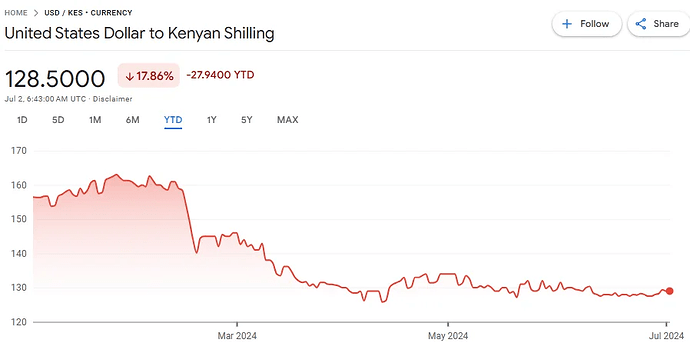

The Kenya shilling has been the best-performing currency this year, mainly because money is flowing into Kenya as global inflation declines. Some might argue that avoiding a debt default played a role, but a few million dollars in repayments wouldn’t be enough to sway serious investors.

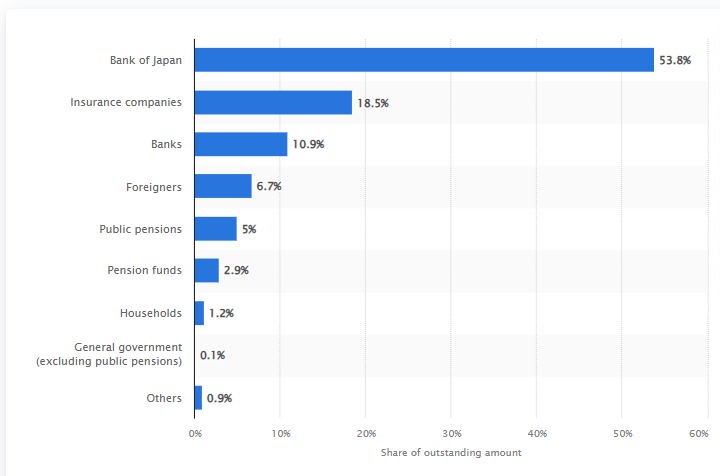

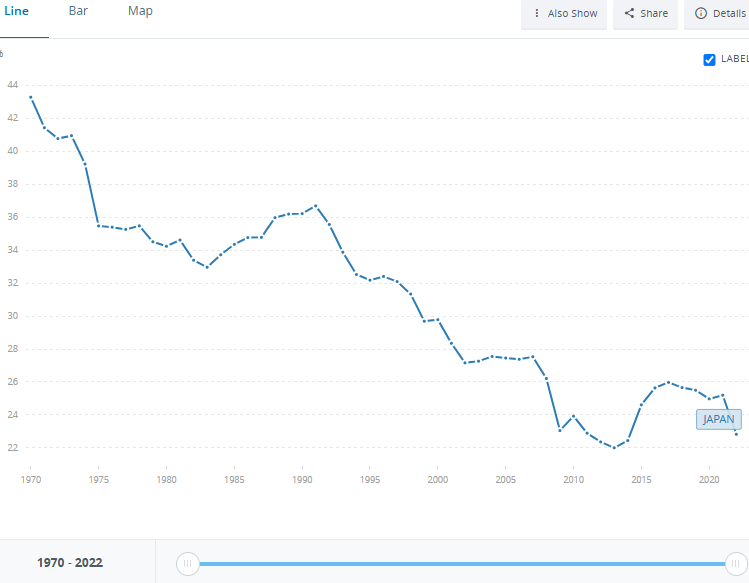

In my view, raising taxes would harm Kenya’s economy. Even if we clear our debts, lower investment would shrink GDP, increasing the debt-to-GDP ratio as the economy contracts. Recovering from a GDP slump is tough—just look at Japan. Since the 1980s, their economy has struggled to grow, with inflation remaining stagnant for decades. It only picked up recently after the yen weakened so much that foreign investors found it incredibly cheap.

Don’t be misled, our debt-to-GDP ratio is fine. Even as a second-rate economist, I know this—so who exactly is advising our government? We need justice for those who lost their lives needlessly and accountability for how our taxes are used.